The term “doublethink” is coined by George Orwell in his renowned novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. In the novel, citizens are brainwashed to accept two conflicting beliefs as truth, knowing them to be contradictory but believing in both. By legitimizing its unethical acts and ridiculous demands imposed on the citizens, the totalitarian regime holds its power and authority. Among the examples in the book, the three slogans of the Party – “War is Peace”, “Freedom is Slavery”, and “Ignorance is Strength” – are the most famous.

Brainwashing is more common than many might have thought. People who lack professional knowledge on a particular subject, who process a certain degree of authoritarian personality, and who worship rules are among those who would be the most easily gaslighted. Some who are brainwashing the others do not actually believe in the propaganda, but doing so because they see it as the most likely way to get what they want (or to protect what they already have) – power, money, fame etc.

This piece lists some examples commonly found within some avant-garde music lovers and advocators.

Alternative title 1: Suite in A minor

Alternative title 2: Unterweisung im Tonsatz [2]

Brainwashing is more common than many might have thought. People who lack professional knowledge on a particular subject, who process a certain degree of authoritarian personality, and who worship rules are among those who would be the most easily gaslighted. Some who are brainwashing the others do not actually believe in the propaganda, but doing so because they see it as the most likely way to get what they want (or to protect what they already have) – power, money, fame etc.

This piece lists some examples commonly found within some avant-garde music lovers and advocators.

Alternative title 1: Suite in A minor

Alternative title 2: Unterweisung im Tonsatz [2]

On Craftsmanship

Rough is great.

Craftsmanship, the one thing that distinguishes a good piece from a bad one, is not something many avant-garde music lovers and advocators care a lot. As long as some basic criteria are met – for example, no “cantabile” melody, no clearly perceptible meters, no identifiable harmonic progressions, and with sections clearly defined by texture/ gestures that reach a certain length (the more unbearably long the better), and with a certain degree of coherence – they will say the piece is “great”.

Parameters that they usually do not care a lot include, but not limited to: idiomaticity (they will blame the performers who are unable to play something specified), practicality (for example, writing a piece that requires 4 helicopters, or 100 mechanical metronomes [3]), melodic shape and direction, the play with varying phrase lengths [4] and constructions, harmonic tension and release and the drama resulted from a change of pitch centre/ collection used.

One might notice that when they criticize non-avant-garde music, they are not looking at the details; when they praise avant-garde music, they are not looking at the details neither. Most of the content - pitches, rhythm, instrumentation…even the length of sections can be greatly altered, and they will still say it is “great”.

If you critically point to the technical weaknesses (of which there are many) of the pieces they love, they might abruptly abandon their idea that those pieces are “superior”, but to say, “whether a piece is great/ effective is highly subjective”. If you are not very critical, they will simply look down on you, and consider you not “intellectual” enough to understand the “greatness” of those rough works.

If whether a piece is superior is “highly subjective”, then the whole idea of compositional techniques and craftsmanship are also “highly subjective”. What is the point of studying music composition? Another question is, how to judge that one piece is better than another? (see also “On Content” and “On Audience”)

“On Craftsmanship” fulfills a number of the basic criteria, and it is more or less “unexpected” (see also “On Rhythm”) while being highly organic, and it provides some gestures – like glissandos and clusters – that will gain avant-garde music advocators’ “approval”. Is it not great?

Alternative title 1: Prelude

Alternative title 2: I am trying to slap a mosquito, but it turns out to be a bee

Alternative title 3: Molecular Collisions

Rough is great.

Craftsmanship, the one thing that distinguishes a good piece from a bad one, is not something many avant-garde music lovers and advocators care a lot. As long as some basic criteria are met – for example, no “cantabile” melody, no clearly perceptible meters, no identifiable harmonic progressions, and with sections clearly defined by texture/ gestures that reach a certain length (the more unbearably long the better), and with a certain degree of coherence – they will say the piece is “great”.

Parameters that they usually do not care a lot include, but not limited to: idiomaticity (they will blame the performers who are unable to play something specified), practicality (for example, writing a piece that requires 4 helicopters, or 100 mechanical metronomes [3]), melodic shape and direction, the play with varying phrase lengths [4] and constructions, harmonic tension and release and the drama resulted from a change of pitch centre/ collection used.

One might notice that when they criticize non-avant-garde music, they are not looking at the details; when they praise avant-garde music, they are not looking at the details neither. Most of the content - pitches, rhythm, instrumentation…even the length of sections can be greatly altered, and they will still say it is “great”.

If you critically point to the technical weaknesses (of which there are many) of the pieces they love, they might abruptly abandon their idea that those pieces are “superior”, but to say, “whether a piece is great/ effective is highly subjective”. If you are not very critical, they will simply look down on you, and consider you not “intellectual” enough to understand the “greatness” of those rough works.

If whether a piece is superior is “highly subjective”, then the whole idea of compositional techniques and craftsmanship are also “highly subjective”. What is the point of studying music composition? Another question is, how to judge that one piece is better than another? (see also “On Content” and “On Audience”)

“On Craftsmanship” fulfills a number of the basic criteria, and it is more or less “unexpected” (see also “On Rhythm”) while being highly organic, and it provides some gestures – like glissandos and clusters – that will gain avant-garde music advocators’ “approval”. Is it not great?

Alternative title 1: Prelude

Alternative title 2: I am trying to slap a mosquito, but it turns out to be a bee

Alternative title 3: Molecular Collisions

On Intellect I

Negligence is intellectual.

Avant-garde music lovers think avant-garde music is intellectual, and thus superior. It is intellectual mainly because they are usually highly tied to mathematics, physics, or some philosophies. Serialism and integral serialism are two examples. Yet how is transcribing something mathematical/ scientific into musical notes intellectual if there is no added greatness? For example, is making a sudoku with musical notes great if it sounds arbitrarily organized (see also “On Audience”)? If one appreciates the logic-based puzzle, is that not the credit should go to the one who invented sudoku instead? Are these “scientifically-driven” music compositions not intellectual only if they are at least refined (see also “On Craftsmanship”)?

AI can easily generate tons of serial pieces in minutes; AI could also follow the basic composition requirements and replace those composers very soon, if not now. What is even more curious about the idea of “intellect” in these avant-garde music is that those composers seem to defeat their own purpose at times. Check out, for example, how Webern employed his carefully designed tone row in the first movement of his symphony, or how he orchestrated Bach’s Ricercar a6.

“On Intellect I” is built on the Fibonacci sequence. Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers in which a number is the sum of the previous two. It typically begins with 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5. There is a fairly wide range of application of the series, and it could also be found in the nature. In this piece, it is applied to the number of attacks in a particular musical layer.

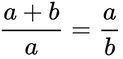

In addition, “On Intellect I” is structured with the golden ratio. Two positive numbers are in a golden ratio if:

Negligence is intellectual.

Avant-garde music lovers think avant-garde music is intellectual, and thus superior. It is intellectual mainly because they are usually highly tied to mathematics, physics, or some philosophies. Serialism and integral serialism are two examples. Yet how is transcribing something mathematical/ scientific into musical notes intellectual if there is no added greatness? For example, is making a sudoku with musical notes great if it sounds arbitrarily organized (see also “On Audience”)? If one appreciates the logic-based puzzle, is that not the credit should go to the one who invented sudoku instead? Are these “scientifically-driven” music compositions not intellectual only if they are at least refined (see also “On Craftsmanship”)?

AI can easily generate tons of serial pieces in minutes; AI could also follow the basic composition requirements and replace those composers very soon, if not now. What is even more curious about the idea of “intellect” in these avant-garde music is that those composers seem to defeat their own purpose at times. Check out, for example, how Webern employed his carefully designed tone row in the first movement of his symphony, or how he orchestrated Bach’s Ricercar a6.

“On Intellect I” is built on the Fibonacci sequence. Fibonacci sequence is a series of numbers in which a number is the sum of the previous two. It typically begins with 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5. There is a fairly wide range of application of the series, and it could also be found in the nature. In this piece, it is applied to the number of attacks in a particular musical layer.

In addition, “On Intellect I” is structured with the golden ratio. Two positive numbers are in a golden ratio if:

, where a > b.

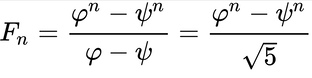

In the second section, the left-hand part persistently presents a polyrhythmic figure with golden ratio as approximated by the Fibonacci sequence. Notice that the Fibonacci numbers (Fn) and the golden ratio are related by the following formula:

In the second section, the left-hand part persistently presents a polyrhythmic figure with golden ratio as approximated by the Fibonacci sequence. Notice that the Fibonacci numbers (Fn) and the golden ratio are related by the following formula:

The pitches in “On Intellect I” are organized with a derived row. It is a twelve-tone row with non-overlapping segments belonging to the same set class; in this piece, it is a (016). The interval classes between each pair of segments are 1, 3 and 5 respectively, which are numbers taken from the Fibonacci sequence. The intervals in the sc(016) are not always presented explicitly (which is curious if we think about the purpose of constructing a row in an “intellectual” way, but is common in serial compositions), and the “Fibonacci intervals” further hide the overwhelming use of interval classes 1 and 6. The use of palindromic figure in the piece is another tribute to Webern.

P.S. I never think golden ratio works in music since music is an art of time rather than an art of space. One cannot grasp the whole structure of the timeframe at any time as one cannot anticipate the length of each section. Also, how do the executions of tempo and tempo changes affect the perception of the golden ratio? Therefore, the use of golden ratio in music is (to me) more a gimmick than a device that help refine the structure.

P.S. I never think golden ratio works in music since music is an art of time rather than an art of space. One cannot grasp the whole structure of the timeframe at any time as one cannot anticipate the length of each section. Also, how do the executions of tempo and tempo changes affect the perception of the golden ratio? Therefore, the use of golden ratio in music is (to me) more a gimmick than a device that help refine the structure.

Alternative title 2: Artificial pseudo intelligence

On Harmony

Indistinctive is personal.

When those avant-garde music advocators ask composers to write something “unique” and “personal”, they are really asking them to follow the mainstreams – some (old) [5] trends. When composers came up with something else, these more personal music will be considered failures to meet the “standard”.

These avant-garde music advocators usually use the term “personal harmonies” to refer to chords with many different pitch classes, preferably highly chromatic and even better if they involve microtones. Yet, how “personal” are these chords? Chords with rich pitch content could be easily found since the early 20th century, and composers of different stylistic backgrounds have been using them in tons of compositions.

Those in an atonal context are even more indistinctive because they usually lack identities. Many people can differentiate a major triad from a minor triad, maybe even able to differentiate the voicing, and perhaps also able to tell the difference between a C major chord and a F# major chord. It is because these chords have identities, especially when heard within a musical context – so we can hear progressions and can feel the different degrees of tension generated by different chords within a tonal piece. However, in a highly chromatic chord, the overtones that come with each note might muddy the sound. As a result, it could be very difficult to differentiate one such muddy sound from another. In addition, many atonal music composers construct chords not based on the sound but on numbers (for example, many serialists and some spectralists), so there come several questions: can those composers recognize their own harmonies by sound? Some numeric selections are common (e.g. sc(014)), how unique are these chords? How can one be sure if the same chord has not been used numerous times? Furthermore, there are also many composers who do not care about harmonies, the “chords” are merely a result of two or more melodic lines sounding together. Are these “chords” distinctive or personal at all, if they cannot even tell you what “chords” are there? And how about clusters? Avant-garde music advocators seldom challenge if clusters are “personal”, but how personal can clusters be?

“On Harmony” quotes and alludes to several famous chordal passages from the Western Classical repertoire written between the mid-19th century to the early 20th century, can you recognize them? If the answer is “yes”, why? They are all common, “impersonal” triads and seventh chords (except for the “Petrushka chord”).

Indistinctive is personal.

When those avant-garde music advocators ask composers to write something “unique” and “personal”, they are really asking them to follow the mainstreams – some (old) [5] trends. When composers came up with something else, these more personal music will be considered failures to meet the “standard”.

These avant-garde music advocators usually use the term “personal harmonies” to refer to chords with many different pitch classes, preferably highly chromatic and even better if they involve microtones. Yet, how “personal” are these chords? Chords with rich pitch content could be easily found since the early 20th century, and composers of different stylistic backgrounds have been using them in tons of compositions.

Those in an atonal context are even more indistinctive because they usually lack identities. Many people can differentiate a major triad from a minor triad, maybe even able to differentiate the voicing, and perhaps also able to tell the difference between a C major chord and a F# major chord. It is because these chords have identities, especially when heard within a musical context – so we can hear progressions and can feel the different degrees of tension generated by different chords within a tonal piece. However, in a highly chromatic chord, the overtones that come with each note might muddy the sound. As a result, it could be very difficult to differentiate one such muddy sound from another. In addition, many atonal music composers construct chords not based on the sound but on numbers (for example, many serialists and some spectralists), so there come several questions: can those composers recognize their own harmonies by sound? Some numeric selections are common (e.g. sc(014)), how unique are these chords? How can one be sure if the same chord has not been used numerous times? Furthermore, there are also many composers who do not care about harmonies, the “chords” are merely a result of two or more melodic lines sounding together. Are these “chords” distinctive or personal at all, if they cannot even tell you what “chords” are there? And how about clusters? Avant-garde music advocators seldom challenge if clusters are “personal”, but how personal can clusters be?

“On Harmony” quotes and alludes to several famous chordal passages from the Western Classical repertoire written between the mid-19th century to the early 20th century, can you recognize them? If the answer is “yes”, why? They are all common, “impersonal” triads and seventh chords (except for the “Petrushka chord”).

If those avant-garde music advocators argue by pointing to the musical context in which the harmonies appear, then how to understand the followings? 1. They did not care the context when they criticized those “impersonal harmonies”, quite often they even failed to label the chords correctly, like looking at the piano left-hand part without looking at the right-hand part, or assuming a certain harmony is used by looking at its surrounding harmonies etc.; 2. they did not care about the progression if the chords are “impersonal”- for example, whether a IV6 is followed by a V, ii6, I64, iv, It6, viiØ42/vi, or even V7/♭II, ♭II64, or other non-functional chords, as long as the progression sounds smooth they will criticize it as “straight forward”; nor do they care if the same chord in the same context is followed by a different chord the second time; 3. if they point to other musical parameters (like musical gestures that follow) when they try to defend the avant-garde music they like, then they have departed from their initial focus and argument [6]; 4. I have changed the musical context from the original pieces of which I quoted, including what preceded and what followed, the chord spacings, register, and even the exact pitch contents, and I also added counterpoint – why can one still recognize them?

Is the whole idea of “personal harmony” a false premise?

P.S. 1 Even the “simplest” tonal passage in this movement is not “basic” at all – and I mean it on at least three levels.

P.S. 2 The opening and ending of this movement feature the same melody with different harmonizations (did you noticed that they are different?). If I say they are personal, I believe many composers out there would object and say that they can do the same – am I right?

P.S. 3 How you would response if I claim that the very last chord in the movement (arpeggiated) is unique in the entire history of music?

Alternative title 1: Sarabande and Waltz

Alternative title 2: Fantasy of a Common Man

P.S. 1 Even the “simplest” tonal passage in this movement is not “basic” at all – and I mean it on at least three levels.

P.S. 2 The opening and ending of this movement feature the same melody with different harmonizations (did you noticed that they are different?). If I say they are personal, I believe many composers out there would object and say that they can do the same – am I right?

P.S. 3 How you would response if I claim that the very last chord in the movement (arpeggiated) is unique in the entire history of music?

Alternative title 1: Sarabande and Waltz

Alternative title 2: Fantasy of a Common Man

On Newness I

Old is new.

Sometimes when avant-garde music advocators are trying to defend the weaknesses of avant-garde music, I hear them say “but it is new!”, as if being new is the most important, if not the only, criteria to judge a composition; as if being refined, captivating, or having emotional, philosophical, or even spiritual content etc. are irrelevant (see also “On Craftsmanship” and “On Content”).

Why being “new” is such an overriding need, as if composers are just YouTubers on trendy matters? How new were Bach’s late works, Brahms’s symphonies, or Rachmaninov’s symphonies in their time? On the other hand, are Rebel’s Les élémens (a late Baroque ballet which begins with dissonant clusters), Haydn’s Symphony no.45 (almost all the orchestral members left the stage by the end of the piece) or Liszt’s “omnitonal” pieces the most highly regarded pieces in the history of music [7]? At least within the avant-garde music cult?

Moreover, when a new idea comes up and is well-received, the composer will just continue with the same approach again and again, and there will be numerous followers worldwide. Are all those pieces after the first one new? Original?

And how to define what is “new”? Much aesthetics from the Second Viennese School remain after more than a century, and some of their music still sound pretty like contemporary music. For how old is a piece considered new? Is an Ivesian piece new? A Ligetian piece new? A Lachenmannian piece new? A Birtwistlian piece new? And how about Piazzollaian or Sondheimian pieces? Check the years of compositions of their celebrated works. And think about this: the first floppy disk [8] was invented around the time minimalistic music emerged and the floppy disks became commercially available when spectral music arose.

Why blindly chase after the idea of “newness” when it usually just means following some relatively newer trends? Can you tell how fast they grow old and become passé (see also “On Cliché”)? And what is left about these rough pieces when they are no longer new? To quote Lachenmann’s words, can you not sense the “stale, implausible, anachronistic, dissonant” of the avant-garde music [9]?

Alternative title 1: Interlude

Alternative title 2: Interstellar messages [10]

Old is new.

Sometimes when avant-garde music advocators are trying to defend the weaknesses of avant-garde music, I hear them say “but it is new!”, as if being new is the most important, if not the only, criteria to judge a composition; as if being refined, captivating, or having emotional, philosophical, or even spiritual content etc. are irrelevant (see also “On Craftsmanship” and “On Content”).

Why being “new” is such an overriding need, as if composers are just YouTubers on trendy matters? How new were Bach’s late works, Brahms’s symphonies, or Rachmaninov’s symphonies in their time? On the other hand, are Rebel’s Les élémens (a late Baroque ballet which begins with dissonant clusters), Haydn’s Symphony no.45 (almost all the orchestral members left the stage by the end of the piece) or Liszt’s “omnitonal” pieces the most highly regarded pieces in the history of music [7]? At least within the avant-garde music cult?

Moreover, when a new idea comes up and is well-received, the composer will just continue with the same approach again and again, and there will be numerous followers worldwide. Are all those pieces after the first one new? Original?

And how to define what is “new”? Much aesthetics from the Second Viennese School remain after more than a century, and some of their music still sound pretty like contemporary music. For how old is a piece considered new? Is an Ivesian piece new? A Ligetian piece new? A Lachenmannian piece new? A Birtwistlian piece new? And how about Piazzollaian or Sondheimian pieces? Check the years of compositions of their celebrated works. And think about this: the first floppy disk [8] was invented around the time minimalistic music emerged and the floppy disks became commercially available when spectral music arose.

Why blindly chase after the idea of “newness” when it usually just means following some relatively newer trends? Can you tell how fast they grow old and become passé (see also “On Cliché”)? And what is left about these rough pieces when they are no longer new? To quote Lachenmann’s words, can you not sense the “stale, implausible, anachronistic, dissonant” of the avant-garde music [9]?

Alternative title 1: Interlude

Alternative title 2: Interstellar messages [10]

On Content

Music is not the sound.

When avant-garde music lovers and advocators praise a piece, they are usually not referring to the music – the sound (as long as they fulfill some basic criteria – see also “On Craftsmanship”), but the idea behind. Numerous examples could be cited: one classic example being Cage’s 4’33” (they find it a genius take to challenge the concept of “music”), another example could be Boulez’s Structures I (they appreciate the mathematics and the rejection of the past). If you laugh at the sound, saying that they sound random, avant-garde music lovers will look down on you – the greatness is not about the sound.

The sound - the music - is just a by-product. How the musical elements are put together are irrelevant, but how the extra-musical elements are put in the score matters; how all those subtle relations among the musical elements and even the architecture of the piece work together are irrelevant, but how complex the score looks matter (see also “On Complexity” [11]); how one crafts a composition is irrelevant, but how one presents the composition matters. Throw people philosophical ideas (the more abstract the better) or scientific findings (the more complicated, the lesser known the better); if people challenge the musical aspects, laugh at them. Be a good salesman in the academia setting means being a great composer. Check out the court scene in the musical Chicago where the lawyer Billy Flynn sings the song “Razzle Dazzle”.

Let me quote a line from Sondheim’s song, “Having just the vision's no solution, everything depends on execution - the art of making art” [12].

P.S. 1 This movement lasts 43.3 seconds.

P.S. 2 The second alternative title of the movement, Ma, refers to a specific Japanese concept of negative space. This movement is much more intellectual with this title, is it not? (see also “On Intellect I” and “On Intellect II”)

P.S. 3 If I use the second alternative title for the first movement, it would probably be deemed as a student piece; but if I use the third alternative title, it would be deemed much more professional (and perhaps intellectual).

Alternative title 1: Intermezzo

Alternative title 2: Ma

Music is not the sound.

When avant-garde music lovers and advocators praise a piece, they are usually not referring to the music – the sound (as long as they fulfill some basic criteria – see also “On Craftsmanship”), but the idea behind. Numerous examples could be cited: one classic example being Cage’s 4’33” (they find it a genius take to challenge the concept of “music”), another example could be Boulez’s Structures I (they appreciate the mathematics and the rejection of the past). If you laugh at the sound, saying that they sound random, avant-garde music lovers will look down on you – the greatness is not about the sound.

The sound - the music - is just a by-product. How the musical elements are put together are irrelevant, but how the extra-musical elements are put in the score matters; how all those subtle relations among the musical elements and even the architecture of the piece work together are irrelevant, but how complex the score looks matter (see also “On Complexity” [11]); how one crafts a composition is irrelevant, but how one presents the composition matters. Throw people philosophical ideas (the more abstract the better) or scientific findings (the more complicated, the lesser known the better); if people challenge the musical aspects, laugh at them. Be a good salesman in the academia setting means being a great composer. Check out the court scene in the musical Chicago where the lawyer Billy Flynn sings the song “Razzle Dazzle”.

Let me quote a line from Sondheim’s song, “Having just the vision's no solution, everything depends on execution - the art of making art” [12].

P.S. 1 This movement lasts 43.3 seconds.

P.S. 2 The second alternative title of the movement, Ma, refers to a specific Japanese concept of negative space. This movement is much more intellectual with this title, is it not? (see also “On Intellect I” and “On Intellect II”)

P.S. 3 If I use the second alternative title for the first movement, it would probably be deemed as a student piece; but if I use the third alternative title, it would be deemed much more professional (and perhaps intellectual).

Alternative title 1: Intermezzo

Alternative title 2: Ma

On Rhythm

What is anticipated is unexpected.

One of the main skills in the craft of composition is the manipulation of tension of release. A good control of the two can keep the music engaging. Establishing a pattern and departing from it at times has been a way of doing it. For example, effective uses of syncopation and varying phrase lengths can be found in many great pieces written in the common practice period.

Many avant-garde composers, however, seek to construct a piece that is not expected at any given moment, at least in terms of rhythmic organization. They avoid establishing a perceivable meter, and one common way to do it is frequently changing the meter and/or putting irregular accents (like some passages in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring), another common way being avoiding metrical accents at all so that the music sounds floaty (like the first movement of Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps). For the former, since the music establishes the norm of irregular accents, all those “unexpected” accents are anticipated. One would not feel surprised by any subsequent accents after the first (maybe not even the first). The situation for the latter is similar. IN either case, the idea of release and tension mentioned earlier plays a little role in terms of rhythm in these pieces. One reason why Stravinsky’s works is the contrast between passages with regular accents and those without.

Another reason is that Stravinsky played with rhythm earlier than many (The Rite of Spring was written in 1913). The trick has grown old – it has become more and more expected. However, many avant-garde lovers out there – who care about newness a lot - do not care. As long as it is irregular, they will think it is unexpected and thus, good. To defend, they might exaggerate metrical accents, demonstrating bombastic downbeats so that you will feel stupid about the idea.

P.S. Mozart employed polymeter (with non-aligning bar lines) over a century earlier than Stravinsky did.

Alternative title 1: Toccata

Alternative title 2: Another Rewrite of Spring

What is anticipated is unexpected.

One of the main skills in the craft of composition is the manipulation of tension of release. A good control of the two can keep the music engaging. Establishing a pattern and departing from it at times has been a way of doing it. For example, effective uses of syncopation and varying phrase lengths can be found in many great pieces written in the common practice period.

Many avant-garde composers, however, seek to construct a piece that is not expected at any given moment, at least in terms of rhythmic organization. They avoid establishing a perceivable meter, and one common way to do it is frequently changing the meter and/or putting irregular accents (like some passages in Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring), another common way being avoiding metrical accents at all so that the music sounds floaty (like the first movement of Messiaen’s Quatuor pour la fin du temps). For the former, since the music establishes the norm of irregular accents, all those “unexpected” accents are anticipated. One would not feel surprised by any subsequent accents after the first (maybe not even the first). The situation for the latter is similar. IN either case, the idea of release and tension mentioned earlier plays a little role in terms of rhythm in these pieces. One reason why Stravinsky’s works is the contrast between passages with regular accents and those without.

Another reason is that Stravinsky played with rhythm earlier than many (The Rite of Spring was written in 1913). The trick has grown old – it has become more and more expected. However, many avant-garde lovers out there – who care about newness a lot - do not care. As long as it is irregular, they will think it is unexpected and thus, good. To defend, they might exaggerate metrical accents, demonstrating bombastic downbeats so that you will feel stupid about the idea.

P.S. Mozart employed polymeter (with non-aligning bar lines) over a century earlier than Stravinsky did.

Alternative title 1: Toccata

Alternative title 2: Another Rewrite of Spring

On Audience

Pleasing target audiences is not pleasing audiences.

Avant-garde music is unwelcome from the beginning. Schoenberg might have thought that his music was only one step away from Wagner’s highly acclaimed and beloved ones, and so audiences would embrace his atonal works. However, his experiments turned out to be a failure, at least in terms of their receptions at the time (and to a large extent, till now). Since then, there are composers who hate audiences.

They do not consider it is their lack of skills that turn audiences away (see also "On Craftsmanship"), but it is the audiences who lack the “intellect” to understand their arts (see also “On Intellect I” and “On Intellect II”). They even teach young composers not to write music “to please the audiences”. This idea is questionable in several ways.

Firstly, they do want to please their audiences – those who share the same avant-garde aesthetics with them, and those who like their works. They are happy when audiences and performers come to them and express how they like the music; they are happy when they get an award or get a job because of their compositions; they are happy when young composers follow their footsteps… The circle works like a cult that comprises people who cannot escape past traumas, as if the anger of the old Schoenberg still lives in them.

A second question is, if audiences do not matter, does the idea of “compositional technique” – which concerns the craft of continuously engaging the audiences and leave them an impact - still matter? No matter how they define “audience”, this question applies. If the music is only valued by the idea behind the music, does it mean that the execution of details – the craft – does not matter (see also “On Craftsmanship” and “On Content”)? How can they judge the greatness of one piece from the other then? If they think the details matter, are they trying to appeal to the audiences (no matter how they define)? And is it not the composer themselves the first audience of a piece?

Moreover, within the avant-garde circle, some composers’ works are more frequently programmed than the others. Do these composers look down on their audiences (who might like their music for the “wrong” reason), or look down on other composers who cannot appeal to a wider audience? Or would they be afraid that they have fallen to the trap of “pleasing the audience”? How about those whose music are not widely performed – do they look down on composers who are more beloved? Or do they feel jealous? And do they all jealous of composers like Wagner, whose works are intellectual, revolutionary and appeal to numerous people worldwide for over a century?

This is the second movement that follows twelve-tone serialism (a system that is inferior to the tonal system in many ways) in the suite. In this piece, the pitches are organized with Milton Babbitt’s trichordal array, which is basically a musical version of a sudoku [13].

The four voices in the texture represent the four rows of the array (later expanded into eight voices). In addition, three out of the four voices follow a rhythmic pattern, and two of them also follow a dynamics series. In other words, this piece employs the idea of integral serialism. However, the tight mathematical system is continuously “threatened” by the tonal system. The “forbidden” tonal pleasure is at first hidden in the array, but becomes more and more unrestrained as the music proceeds, and finally it takes control over the music. Towards the end, the conflict between the two styles escalates and pushes the music to a frenzied ending.

Alternative title 1: Chaconne – Waltz

Alternative title 2: Babbitt’s [14] Secret Dream

Pleasing target audiences is not pleasing audiences.

Avant-garde music is unwelcome from the beginning. Schoenberg might have thought that his music was only one step away from Wagner’s highly acclaimed and beloved ones, and so audiences would embrace his atonal works. However, his experiments turned out to be a failure, at least in terms of their receptions at the time (and to a large extent, till now). Since then, there are composers who hate audiences.

They do not consider it is their lack of skills that turn audiences away (see also "On Craftsmanship"), but it is the audiences who lack the “intellect” to understand their arts (see also “On Intellect I” and “On Intellect II”). They even teach young composers not to write music “to please the audiences”. This idea is questionable in several ways.

Firstly, they do want to please their audiences – those who share the same avant-garde aesthetics with them, and those who like their works. They are happy when audiences and performers come to them and express how they like the music; they are happy when they get an award or get a job because of their compositions; they are happy when young composers follow their footsteps… The circle works like a cult that comprises people who cannot escape past traumas, as if the anger of the old Schoenberg still lives in them.

A second question is, if audiences do not matter, does the idea of “compositional technique” – which concerns the craft of continuously engaging the audiences and leave them an impact - still matter? No matter how they define “audience”, this question applies. If the music is only valued by the idea behind the music, does it mean that the execution of details – the craft – does not matter (see also “On Craftsmanship” and “On Content”)? How can they judge the greatness of one piece from the other then? If they think the details matter, are they trying to appeal to the audiences (no matter how they define)? And is it not the composer themselves the first audience of a piece?

Moreover, within the avant-garde circle, some composers’ works are more frequently programmed than the others. Do these composers look down on their audiences (who might like their music for the “wrong” reason), or look down on other composers who cannot appeal to a wider audience? Or would they be afraid that they have fallen to the trap of “pleasing the audience”? How about those whose music are not widely performed – do they look down on composers who are more beloved? Or do they feel jealous? And do they all jealous of composers like Wagner, whose works are intellectual, revolutionary and appeal to numerous people worldwide for over a century?

This is the second movement that follows twelve-tone serialism (a system that is inferior to the tonal system in many ways) in the suite. In this piece, the pitches are organized with Milton Babbitt’s trichordal array, which is basically a musical version of a sudoku [13].

The four voices in the texture represent the four rows of the array (later expanded into eight voices). In addition, three out of the four voices follow a rhythmic pattern, and two of them also follow a dynamics series. In other words, this piece employs the idea of integral serialism. However, the tight mathematical system is continuously “threatened” by the tonal system. The “forbidden” tonal pleasure is at first hidden in the array, but becomes more and more unrestrained as the music proceeds, and finally it takes control over the music. Towards the end, the conflict between the two styles escalates and pushes the music to a frenzied ending.

Alternative title 1: Chaconne – Waltz

Alternative title 2: Babbitt’s [14] Secret Dream

On Intellect II

Thoughtful is superficial.

A common propaganda from the avant-garde music advocators is that Romantic music is sentimental, avant-garde music is cerebral; and that the word “sentimental” is used in a rather negative sense, where “cerebral” is used in a positive sense. Very few (if not none) avant-garde music is sentimental, and as I argued, most (if not all) are not intellectual neither (see “On Intellect I”). On the other hand, are Bach’s fugues or Wagner’s Ring cycle, for example, not intellectual? Consider how Bach worked on a four-voice fugue, superimposing the subject in diminution, inversion, augmentation almost at the same time, and still able to keep the music melodically, rhythmically and harmonically convincing and pleasing in his “Contrapunctus 7” of The Art of Fugue, or how Wagner worked on the gigantic operatic cycle, deciding basically every element of the production (lyrics, music, stage direction, etc., and even theatre design), and showing numerous innovations and amazing Craftsmanship in multiple professions, at the same time expressing complex philosophical ideas. Are these pieces not intellectual, musically satisfactory, and might even touch people’s heart deeply or even change their lives? How could those avant-garde music superior in any sense?

There are movies that people enjoy watching by just following the plot, and also contain added layer(s) of meaning to audiences who try to think deeper: what some characters, actions, or props are representing, or how elements in the movie are related. In some movies, even tiny little details in the background carry further meaning (I am referring to things that are more than Easter eggs). Upon deeper reflections or analyses, audiences can get a lot more out of the movie. It is this kind of artwork that I consider intellectual, and it is this kind of details that make a piece personal and unique.

“On Intellect II” is basically the same piece as “On Intellect I”, but most of the pitches are changed. So, the Fibonacci sequence and the golden ratio are still there, but the derived row is gone. Do you find it melodically and harmonically much more satisfactory than “On Intellect I”? Do you find it musically more pleasing/ better crafted? Do you think it is expressing some inner emotions? Or find it more poetic? If the answer is “yes” to any one or more of the above, can you see what I meant by “intellectual”?

Alternative title 1: Poème

Alternative title 2: I hear the dandelion seeds flying [15]

Thoughtful is superficial.

A common propaganda from the avant-garde music advocators is that Romantic music is sentimental, avant-garde music is cerebral; and that the word “sentimental” is used in a rather negative sense, where “cerebral” is used in a positive sense. Very few (if not none) avant-garde music is sentimental, and as I argued, most (if not all) are not intellectual neither (see “On Intellect I”). On the other hand, are Bach’s fugues or Wagner’s Ring cycle, for example, not intellectual? Consider how Bach worked on a four-voice fugue, superimposing the subject in diminution, inversion, augmentation almost at the same time, and still able to keep the music melodically, rhythmically and harmonically convincing and pleasing in his “Contrapunctus 7” of The Art of Fugue, or how Wagner worked on the gigantic operatic cycle, deciding basically every element of the production (lyrics, music, stage direction, etc., and even theatre design), and showing numerous innovations and amazing Craftsmanship in multiple professions, at the same time expressing complex philosophical ideas. Are these pieces not intellectual, musically satisfactory, and might even touch people’s heart deeply or even change their lives? How could those avant-garde music superior in any sense?

There are movies that people enjoy watching by just following the plot, and also contain added layer(s) of meaning to audiences who try to think deeper: what some characters, actions, or props are representing, or how elements in the movie are related. In some movies, even tiny little details in the background carry further meaning (I am referring to things that are more than Easter eggs). Upon deeper reflections or analyses, audiences can get a lot more out of the movie. It is this kind of artwork that I consider intellectual, and it is this kind of details that make a piece personal and unique.

“On Intellect II” is basically the same piece as “On Intellect I”, but most of the pitches are changed. So, the Fibonacci sequence and the golden ratio are still there, but the derived row is gone. Do you find it melodically and harmonically much more satisfactory than “On Intellect I”? Do you find it musically more pleasing/ better crafted? Do you think it is expressing some inner emotions? Or find it more poetic? If the answer is “yes” to any one or more of the above, can you see what I meant by “intellectual”?

Alternative title 1: Poème

Alternative title 2: I hear the dandelion seeds flying [15]

On Newness II

New is old.

Avant-garde music is an old idea. As mentioned earlier (see “Newness I”), much aesthetics from the Second Viennese School remain after more than a century, and some of the contemporary music still sound pretty like those written by the old masters. Yet it is the kind of music that they will consider new, and other newer styles will be considered old.

What could be the possible composition year of “On Newness II”? It shows influences of Classical music of different eras (from Baroque to the 20th century), Jazz music, Japanese animation music, and pop music. Could it have been written before the 21st century? Avant-garde music lovers would probably say it is old, pointing to the use of tonal language, four-bar phrasing etc. But how about the use of clusters, glissandos, “more personal harmonies”, musical quotations and a polystylistic approach? And if they want to frame their stylistic dissatisfactions as technical weaknesses, like “it is too square” …wait, “but it is new!”

P.S. Ernst Oster, a musicologist and music theorist, suggested that Chopin did not publish his now-famous Fantaisie-Impromptu because of its similarities to Beethoven's Piano Sonata No.14, "Moonlight". It is true that they share something in common (in particular, a “quotation” that is highlighted in “On Newness II”), but they are also very different. Is Chopin’s piece new or old in his time?

Alternative title 1: Air (Passacaglia) [16]

Alternative title 2: A Song of Angry Men (The End of the Beginning)

New is old.

Avant-garde music is an old idea. As mentioned earlier (see “Newness I”), much aesthetics from the Second Viennese School remain after more than a century, and some of the contemporary music still sound pretty like those written by the old masters. Yet it is the kind of music that they will consider new, and other newer styles will be considered old.

What could be the possible composition year of “On Newness II”? It shows influences of Classical music of different eras (from Baroque to the 20th century), Jazz music, Japanese animation music, and pop music. Could it have been written before the 21st century? Avant-garde music lovers would probably say it is old, pointing to the use of tonal language, four-bar phrasing etc. But how about the use of clusters, glissandos, “more personal harmonies”, musical quotations and a polystylistic approach? And if they want to frame their stylistic dissatisfactions as technical weaknesses, like “it is too square” …wait, “but it is new!”

P.S. Ernst Oster, a musicologist and music theorist, suggested that Chopin did not publish his now-famous Fantaisie-Impromptu because of its similarities to Beethoven's Piano Sonata No.14, "Moonlight". It is true that they share something in common (in particular, a “quotation” that is highlighted in “On Newness II”), but they are also very different. Is Chopin’s piece new or old in his time?

Alternative title 1: Air (Passacaglia) [16]

Alternative title 2: A Song of Angry Men (The End of the Beginning)

The suite is dedicated to those who are brainwashed to consider themselves superior, and to those who are brainwashing others to be like them.

P.S. 1 If someone who are angry about this piece not arguing with sound counterarguments but react with personal attacks (likely with lies or misleading information), or appeal to authority (e.g. implying that a certain authority could not be wrong), or terminate the conversation, you know that they are likely to have been brainwashed. The more skilful one escapes a predicament by straying off to other topics – may it be another specific area (e.g. when unable to defend the harmonic progression in a piece, they turn to talk about the motivic development), or a board question (e.g. “What is a progression? Why there has to be a progression?”) – or by polarizing a situation and ask you to choose between extremes, or by misleading you that it is the trend/ situation when it is indeed only a small part of the whole picture. Whether they are brainwashed or not, they are certainly brainwashing you.

P.S. 2 Do not get me wrong, everyone can like what they like for whatever reasons, or even without a reason, but do not become part of an authoritarian party.

P.S. 3 More movements will follow.

P.S. 4 Am I the one who is really avant-garde, when the current avant-garde is already part of the establishment?

P.S. 1 If someone who are angry about this piece not arguing with sound counterarguments but react with personal attacks (likely with lies or misleading information), or appeal to authority (e.g. implying that a certain authority could not be wrong), or terminate the conversation, you know that they are likely to have been brainwashed. The more skilful one escapes a predicament by straying off to other topics – may it be another specific area (e.g. when unable to defend the harmonic progression in a piece, they turn to talk about the motivic development), or a board question (e.g. “What is a progression? Why there has to be a progression?”) – or by polarizing a situation and ask you to choose between extremes, or by misleading you that it is the trend/ situation when it is indeed only a small part of the whole picture. Whether they are brainwashed or not, they are certainly brainwashing you.

P.S. 2 Do not get me wrong, everyone can like what they like for whatever reasons, or even without a reason, but do not become part of an authoritarian party.

P.S. 3 More movements will follow.

P.S. 4 Am I the one who is really avant-garde, when the current avant-garde is already part of the establishment?

[1] In this piece, the term “avant-garde” is referring to those “experimental music” that sprang from, and inherited the Second Viennese School aesthetics up till now. I include integral serialists, spectralists and others even if those involved composers oppose to each other’s approach – their central ideas remain the same.

[2] It is the title of Hindemith’s book, which is translated as “The Craft of Musical Composition”.

[3] You might be surprised to know that these examples are not imaginary and are written by renowned composers.

[4] They might argue that they care about varying phrase length. It is true, but what I am referring to is the “play” of expectations and surprises (see “On Rhythm”). Without a pattern in which irregularity works against with, the music often just sound arbitrary (and they might be actually arbitrary written).

[5] Their concept of new and old is also curious, see “On Newness I” and “On Newness II”.

[6] In Hong Kong we call this 搬龍門, which originates from the phrase “moving the goalposts”.

[7] How much you know about these pieces if I did not put the supplementary information? Or when compared to Brahms or Rachmaninov’s symphonies?

[8] A floppy disk is a disk storage having the capacity of 800 KB to 2.8 MB.

[9] Helmut Lachenmann (1995): On structuralism, Contemporary Music Review, 12:1, 93-1. He was referring to the tonal system, but are these adjectives not fit avant-garde music better?

[10] Interstellar messages could take years, decades, or even longer to arrive. When it finally reaches the recipient, the “new message” to them could have been very old and outdated.

[11] “On Complexity” will be premiered later.

[12] From Sondheim’s song “Putting It Together” in his musical Sunday in the Park with George, of which he is both the composer and lyricist.

[13] The array is a table with four rows and four columns, within each row there are four cells of ordered trichord that combine to form an aggregate of all the twelve pitch classes, and similarly, within each column there are four cells of ordered trichord that combine to form an aggregate. Furthermore, each series is designed such that it is hexachordally combinatorial. As a result, each pair of hexachords also from form an aggregate.

[14] To be clear, it is an imaginary person whose last name happens to be Babbitt.

[15] The seed head of the dandelion follows the Fibonacci Spirals.

[16] The (ab)use of generic title since the Second Viennese School composers worth another movement.

[2] It is the title of Hindemith’s book, which is translated as “The Craft of Musical Composition”.

[3] You might be surprised to know that these examples are not imaginary and are written by renowned composers.

[4] They might argue that they care about varying phrase length. It is true, but what I am referring to is the “play” of expectations and surprises (see “On Rhythm”). Without a pattern in which irregularity works against with, the music often just sound arbitrary (and they might be actually arbitrary written).

[5] Their concept of new and old is also curious, see “On Newness I” and “On Newness II”.

[6] In Hong Kong we call this 搬龍門, which originates from the phrase “moving the goalposts”.

[7] How much you know about these pieces if I did not put the supplementary information? Or when compared to Brahms or Rachmaninov’s symphonies?

[8] A floppy disk is a disk storage having the capacity of 800 KB to 2.8 MB.

[9] Helmut Lachenmann (1995): On structuralism, Contemporary Music Review, 12:1, 93-1. He was referring to the tonal system, but are these adjectives not fit avant-garde music better?

[10] Interstellar messages could take years, decades, or even longer to arrive. When it finally reaches the recipient, the “new message” to them could have been very old and outdated.

[11] “On Complexity” will be premiered later.

[12] From Sondheim’s song “Putting It Together” in his musical Sunday in the Park with George, of which he is both the composer and lyricist.

[13] The array is a table with four rows and four columns, within each row there are four cells of ordered trichord that combine to form an aggregate of all the twelve pitch classes, and similarly, within each column there are four cells of ordered trichord that combine to form an aggregate. Furthermore, each series is designed such that it is hexachordally combinatorial. As a result, each pair of hexachords also from form an aggregate.

[14] To be clear, it is an imaginary person whose last name happens to be Babbitt.

[15] The seed head of the dandelion follows the Fibonacci Spirals.

[16] The (ab)use of generic title since the Second Viennese School composers worth another movement.